Climate Change - Cognitive Biases

Why are we still not doing anything? The cognitive biases stopping individuals from taking meaningful action against the global climate emergency.

As summer slips away, it’s become harder than ever to ignore the volume (and intensity) of climate-related disasters that have hit over the past couple of months alone.

The “worst rain for 1,000 years” left dozens dead in China; the record-breaking ‘heat dome’ that incapacitated the Pacific Northwest for weeks killed an estimated 1bn marine animals; fires ravaged Turkey and Greece (releasing even more carbon into the atmosphere in the process); while ‘biblical’ floods in Germany and Belgium killed over 180 people, with many hundreds more missing. Earlier, the sea literally caught fire in the Gulf of Mexico.

Closer to home, the Met Office issued its first-ever extreme heat warning for the UK in a month that also saw intense bursts of rainfall repeatedly flood parts of London and Edinburgh.

These events were followed by the timely publication of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report; a “code red for humanity” which confirms that human-induced climate change is now affecting every region across the globe - with many of these “widespread, rapid and intensifying” changes irreversible for centuries to millennia.

We’re quite clearly living in a global climate emergency. So why don’t we act like it?

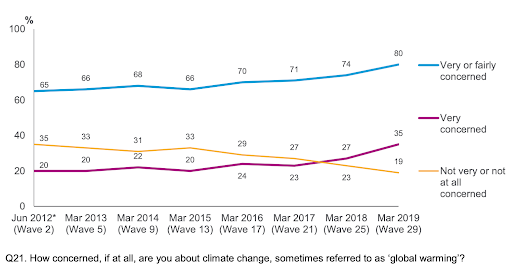

Although it is true that concern for climate change has been growing every year (at least in the UK), we just seem to be carrying on much the same. Flights are picking back up, online deliveries are helping us buy more stuff than ever, and billionaire CEOs, who say all the right things about climate change, have chosen now to start playing out some kind of midlife crisis space race.

Inspired by my colleague Chris’s excellent article on the need to reposition climate change, below are some cognitive biases and thought processes that might be getting in the way of us, as individuals, taking meaningful climate action.

1. Present focus bias

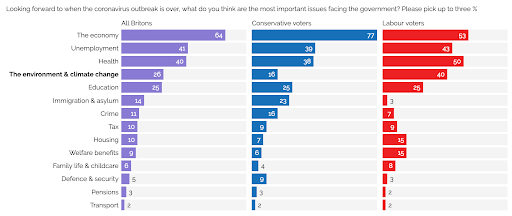

Climate change is easy to dismiss as ‘a problem for another day’, particularly when most of us have plenty of everyday worries that affect us right now. Whether it’s personal finances, health, job security, housing, relationships or family problems, all of these feel much more urgent than distant, or abstract, threats that may affect us years into the future (or that mostly seem to happen on the other side of the planet).

Yes, people are very concerned about climate change - but climate change isn’t one of their immediate concerns. In fact, concern for the climate can often seem like a pursuit reserved for those who don’t have much else to be concerned about. Something for those who’ve cleared their inboxes of most other common worries. You only need to look at the demographics of a typical Extinction Rebellion protest to see this privilege.

Unlike the immediacy of the pandemic, an emergency that pitches targets 25 and 30 years into the future will always find it tough to galvanise societal-level behaviour change right this moment. As for leaders, they’ll be long gone by then - and it’ll be someone else’s problem.

2. Optimism bias

Talking of leaders palming off problems, the last 18 months have shown us what an “it’ll be fine, just because I’ve said it will be” attitude from the top can lead to. This belief in Hollywood endings, that things will always somehow work themselves out in the end, is particularly rife amongst ‘climate engineers’, who confidently predict that climate catastrophe can (and will) be averted via geoengineering - i.e. large-scale manipulation of the environment.

A tendency among many to give more weight to the opinions of successful figures (authority bias), sees this baseless optimism filter down. Confirmation bias, only paying attention to information or sources that confirm your existing beliefs, can result in it taking hold.

See also: the Ostrich effect or Normalcy bias (the refusal to plan for, or react to, a disaster which has never happened before).

3. The ‘what about China?’ effect

Amongst those who have come to accept the reality and urgency of the situation, there’s a common thought that any individual action will ultimately be pointless when held up against the worst offending countries and fossil fuel companies. A doom and gloom narrative around climate change just exacerbates the idea that action won’t make any difference.

China is typically invoked here as the biggest culprit of all; and it's true that a heavy reliance on coal contributed to the country emitting 27% of the world’s greenhouse gases in 2019. The Climate Action Tracker quite rightly lists their contribution as ‘highly insufficient’ - though it does highlight worse offenders.

It’s worth noting that China is home to almost a fifth of the world’s population, ranking as low as 38th for CO2 emissions per capita. In “This Changes Everything”, Naomi Klein points out how the ‘deeply flawed’ emissions accounting system, an “odd relic of the pre-free-trade era” creates “a vastly distorted picture of the drivers of global emissions”:

“[C]ountries are responsible only for the pollution they create inside their own borders - not for the pollution produced in the manufacturing of goods that are shipped to their shores; those are attributed to the countries where the goods were produced.”

It’s well known that many of the world’s electronics, clothes, furniture, toys (etc.) are Made In China and, due to this ‘offshoring’ of emissions, the collective climate impact of much of the stuff we, as individuals, buy ends up on China’s emissions rap sheet. In fact, almost half of the UK’s emissions are embedded in imports - but our national accounts don’t show them.

4. Loss aversion

It’s all well and good encouraging people to consume less, but ‘less’ is generally a tricky proposition to sell. A lot of climate action revolves around this idea: less buying, less flying, less meat and dairy, and generally less of the things many of us are used to having on tap.

People in the West tend to like their lifestyles and don’t want to change (back). As Thaler & Sunstein note, via the mug experiment, “losing something makes you twice as miserable as gaining the same thing makes you happy”.

See also: Status quo bias.

So where do we go from here?

Firstly, we should recognise the progress made in the last two or three years. Whether it’s David Attenborough taking the gloves off, Greta Thunberg and school strikes, climate marches, the declaration of a ‘climate emergency’ (and the adoption of it as a term), or even Tottenham and Chelsea preparing for the world’s first major net-zero football match, levels of awareness, understanding and, as we’ve seen, concern about climate breakdown have all significantly increased.

This has seen many shifts from pre-contemplation (no intention of changing behaviour) to contemplation (aware a problem exists) and even preparation (intent upon taking action) - but there’s still a sense that many actions are too difficult, confusing or out of reach.

The pandemic has shown how our collective actions can make a genuine impact. Fostering this same sense of societal involvement could make the difference - with our tracking showing that a quarter of people agree that it’s not worth them doing things to tackle climate change if others don’t do the same. Consider this:

Cycling Scotland has recorded a 47% increase in people cycling year on year

It was estimated that in lockdown, we wasted a third less food

More than 90% of people who have shopped locally say they will continue to do so

In 2015, just 1.1% of new vehicles registered in the UK were plug-in models. This has now risen to almost 15%

It’s still just a start, but highlighting these new actions that all sorts of people are doing - and celebrating the wins to reinforce the idea we can make a difference - might just nudge enough of us in the right direction. As much as we might like to think otherwise, our attitudes and behaviours are heavily influenced by those around us - i.e. by social norms.

If there’s one thing we’ve recently learned, after all, it's that humans will always be social creatures. Let’s not waste this opportunity.